In a previous blog post I introduced the term ‘Inner gamification’ to indicate the use of game development features to enhance elearning that do not use ‘outer features’ like scores or badges. I since came across another term I like – game inspired design in a diagram shared by @daverage on Twitter.

This second part handles some of the storytelling techniques we can learn from games and shares some opinions on good storytelling.

A story does not make itself, the learner makes it

More and more instructional designers move to scenario based learning, which is a great evolution. Doing this well however is still a challenge. Too often the learner is presented with a long background story to read, followed by a decision making exercise.

In many cases it is necessary for the learner to have all the background information to make correct decisions. Like in real life, the learner should assemble this information from relevant sources so they can construct the story themselves, analyse it and draw conclusions to lead to the right decision. Good game design makes sure the player discovers the story of a situation or character during the game play, and takes action accordingly.

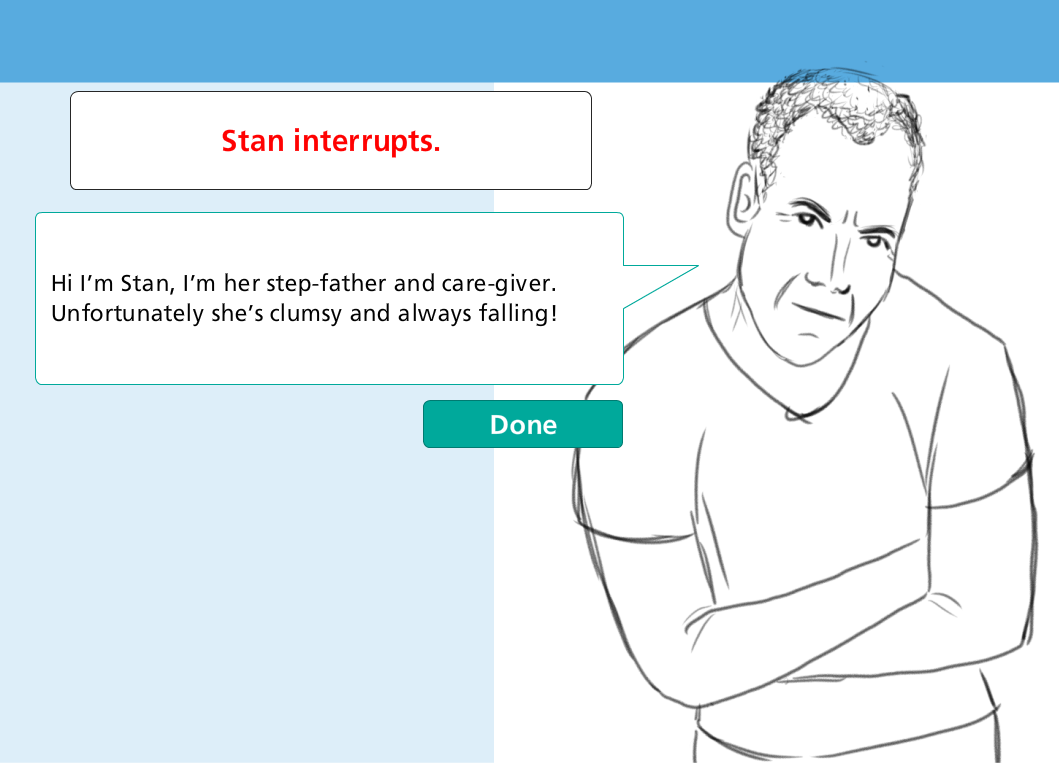

Let the learner piece together the story by a collection of means: reading an e-mail or note, talking to people involved, overhearing conversations, or observing an action/scene. Try to add emotions where relevant – in the example shown here (with thanks to @moodlelair who designed this course) an overpowering relative keeps a nurse from talking to a patient. The learner draws certain conclusions from this and makes the story in their head.

Real stories are not always complete

“But what if they miss pieces of information?”, you ask. “That is intrinsic to good scenario writing!”, I say. Missing a piece of information or interpreting it in your own, subjective way is how things happen in real life. The “safe environment” of a training allows the learner to learn from this. If they make an uninformed decision this can be pointed by consequences that are designed to change the learner’s attentiveness and insights in real life situations. You, as the instructional designer, can point them back to the missed info and say ‘You did not consult these notes, so your conclusion was based on incomplete information’ or ‘ You forgot to talk to this interested party, so you took the wrong action’.

Do not provide information all at once, no matter what techniques you use. Your learner could discover more information while the story unfolds, by making the right decisions, e.g. order an Xray for a patient providing more medical insight or send an email to someone who provides them with a relevant document.

In a twist of plot, your learner may also be given biased information by some of the ‘players’ in the scenario. Stan, in the screen example above, explains how the patient got hurt but the learner will feel that they will need to handle this information cautiously in their decision making.

Cut!

Larger games often use “cut scenes” to move the story along. The player sits and watches a part of the story in which they are not actively involved, but it explains motives, feelings, movement of the action to another background. Game designers know these scenes should be short and to the point as they actually ‘break’ the game play.

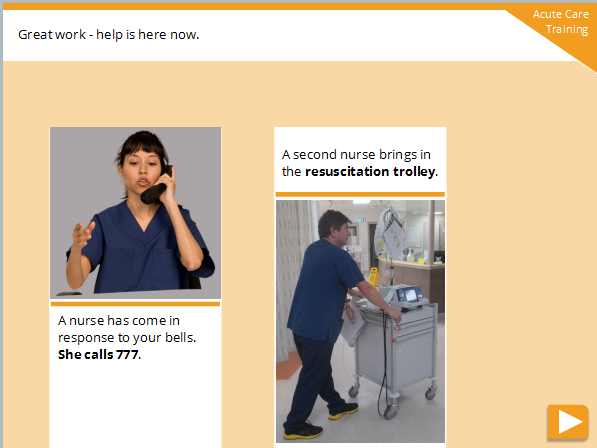

An interactive scenario-based course can benefit from this technique to bring the learner to the next action. A part of your scenario is not in the hands of the learner, e.g. while you are administering first aid someone else calls for assistance. A short cut scene showing this makes your story more complete and lifelike.

An interactive scenario-based course can benefit from this technique to bring the learner to the next action. A part of your scenario is not in the hands of the learner, e.g. while you are administering first aid someone else calls for assistance. A short cut scene showing this makes your story more complete and lifelike.

As in games, these short scenes should be limited and have a clear purpose to move the story along to the next interaction required from the learner.

The ID knows more… you can feel it

Over the past years, J.K. Rowling has revealed little bits and pieces in her Twitter and blog feeds about Harry Potter and his companions – things that are not in the books, but she knows them (e.g. why Harry named his son after Severus Snape). That these stories are world news, shows the strength of her storytelling.

Good learning and game stories should also provide a feeling of ‘more’. You, the designer, know the full background history, the intimate dreams and aspirations of your main character even when these details are unnecessary to the learning and not revealed. Invisible but powerful, this will make the reader more connected to your story.